Identity and the curation of sites of modern heritage

As I write this blog, all of us here at Tokyo College, and all around the world, are living in truly abnormal times. For the more fortunate among us, the novel corona virus, aka COVID-19, has merely (!) upended and constrained our daily life routines, personal and professional, and put all future planning into a state of suspended animation. For others, it has been a profound threat to economic survival. And for too many, it has been a threat to life itself. In that context, it feels both odd, yet necessary, to write something for this blog space that is NOT about the virus. If for no other reason than to prevent the normalization of the abnormal.

My stay at Tokyo College has allowed me to get fully underway on a research project I’ve been hoping for some years to undertake: a study of the public history of sites of Japan’s first industrial revolution. Fortunately, before the state-of-emergency put a stop to field research trips, I was able this winter to visit several of the locations I had been planning to examine. What follows is a brief interim sketch—more a “sketch” than a proper “report”. It is based on a brief presentation I made in early April to the Tokyo College study group on identity, and it attempts to connect my own research project to the themes of this collaborative undertaking.

Several years ago, I realized that many of the places I had studied early in my career had changed from living entities to modern fossils. My dissertation and first book looked at the history of labor relations in sites of heavy industry, primarily shipyards and steel mills, with a sideways glance at coal and copper mines. I examined the period from the 1850s to the 1950s, and when I did the research in the late 1970s, most of the places I studied were still operating. That is no longer the case. Many of the most famous sites of Japan’s industrial revolution have shut down. In some cases, they’ve become sites of high-rise buildings: the Yokohama Dock Company is buried under the Landmark Tower in Yokohama; the Ishikawajima shipyard on Tsukishima in the heart of Tokyo rests under two luxury condominium towers. In other cases, from the Joban coal fields in Tokyo’s “backyard” to the coal mines in Kyushu, thousands and thousands of solar panels sit in neat rows on land once covered by rows of coal miner housing. But in other cases, museums have been built near the pitheads of major mines, to explain to local people and a wider world their notable history. And in some cases, the buildings and machinery, or the mine pit entrances, have been preserved or restored and opened for tourists ranging from local school children to visitors from overseas.

The 2015 controversy over UNESCO’s granting of World Heritage status to 23 industrial sites in 8 prefectures—the Meiji Industrial Revolution World Heritage Sites—drew my attention to the question that drives my research. Who curates and narrates the history of these places, once operating businesses, now sites of memory and heritage? What histories are told, by whom, and with what audience in mind? And who listens?

The official history presented to UNESCO by the Japanese government was a simple one, crafted in part to satisfy the requirement that a World Heritage Site, or cluster of sites, needed to exemplify in some way what UNESCO calls “outstanding universal value (OUV).” By that, UNESCO means “cultural and/or natural significance which is so exceptional as to transcend national boundaries and to be of common importance for present and future generations of all humanity.” For the Japanese government, these sites possessed “OUV” because they gave material evidence of how Japan “was the first non-Western nation to industrialize through a self-determined strategy.”

The government presented the history of these sites to UNESCO purely as evidence of a proud national achievement at a time when most all “the rest” were coming under the domination of “the West.” This interpretation struck me not so much as wrong but as incomplete and thus fundamentally misleading. It struck the government of South Korea and the wider public in Korea as not only incomplete but also offensive because the only history spoken of was that of the late Tokugawa era through 1912, the end of the reign of the Meiji emperor. This temporal frame allowed the government to avoid addressing the brutal conditions imposed on laborers drafted and brought against their will from the Korean peninsula to work in these and many other mines and factories. I share this critical view of “history in a box”, that brackets off later times. It not only obscures the brutalities of wartime. It elides the key, and often turbulent, role of these facilities in Japan’s postwar economic and social history.

But beyond the problematic temporal frame, I found equally troubling the one-sided presentation of the history of the Meiji era itself. That is not only a history of impressive technological import, entrepreneurship, and economic development. It is equally a history of harsh treatment of laborers, both women and men, both relatively free and entirely unfree—for prisoners were an important component of the mining labor force from Kyushu to Hokkaido. It is also a history of frequent accidents taking hundreds of lives. And it is a history of protest at these conditions, the partial amelioration of conditions over time, and the building of impressive community and solidarity among the miners.

With these concerns in mind, I have been looking to see whether the arid story presented by the government to UNESCO was the main or the only story being told on the ground, as it were, by the curators and guides and other local actors. This inquiry is still in its early stages, but I have been struck so far by the significant gaps between richly varied local presentations and the formal state presentation of this heritage in nationally “Japanese” and cheerful terms. An impressive range of local actors and organizations, such as the founder and members of the “Omuta-Arao Fan Club” (Mitsui Miike Mine) or the veteran curator of the Tagawa Coal Mining Museum (home to the extraordinary drawings and paintings of Yamamoto Sakubei) and many others, are passionately devoted to the preservation of these sites of industrial heritage and the presentation of a rich multi-sided history.

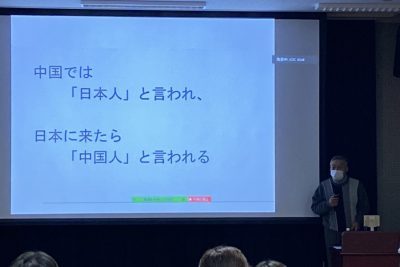

In relation to the Tokyo College project on identity, what I find most notable is the multiplicity of identities revealed by, or attribute to, the people and groups at the heart of the industrial heritage story, as presented by curators and other local actors. A “Japanese identity,” explicitly or even implicitly, is not prominent in self-presentation or the framing provided by others.

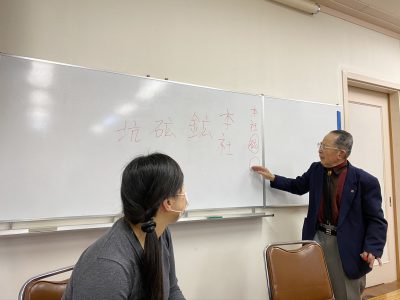

A former miner at the Mitsubishi Mine in Chikuho, now 89 years old and an occasional story-teller at the Tagawa museum, spoke to me and other visitors for nearly two hours without once mentioning “Japan” as a point of reference in his career. He was, from start to finish, a Mitsubishi man. The company was, for him, the heart of his identity, with occasional reference to his town and his family.

About 100 kilometers to the southwest of Tagawa, the former miners who worked as volunteer guides at the Miike mine sites in Omuta and Arao spoke from the perspective of their union, or the company, or the local community. The founder of the Omuta-Arao Fan Club, whose only personal connection is that of a local resident, has tirelessly recorded oral histories as well as organized walking tours of the mining sites. For him, the town’s past must be preserved and passed on to future generations in the community as local far more than national heritage.

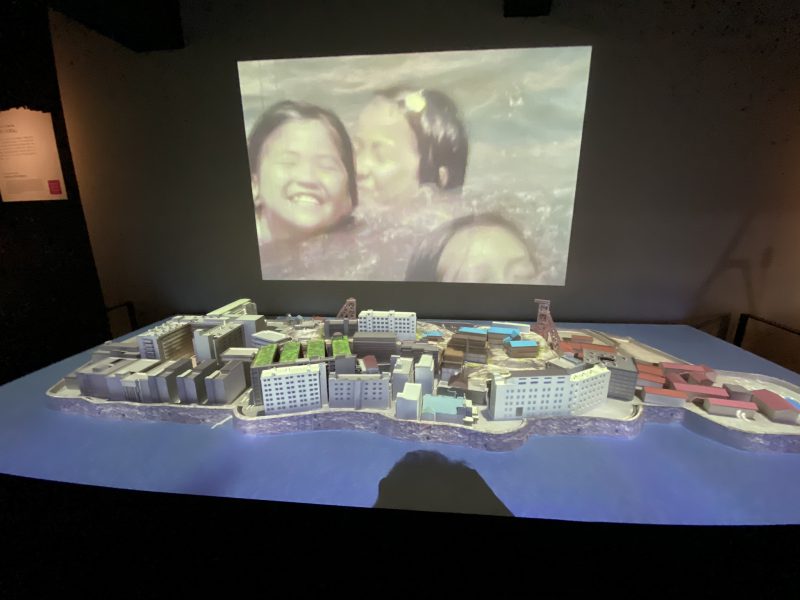

The former residents of Gunkanjima (Battleship Island; formally speaking, Hashima) who served as guides at the Gunkanjima Digital Museum or accompanied the boat trip to the island from start to finish talked of themselves as “islanders” (島民). They were not themselves miners, but the children of miners who grew up on the island. For them, island life for a child was one of rich community. They spoke somewhat resentfully of the widespread use of the nickname “Battleship Island” as the label for their home. For them, it “Hashima”. These nostalgic recollections of childhood play with friends were accompanied—and to some extent belied by—a critical view of actual work in the mines—none of those I spoke to had for a moment considered entering the mines as their fathers had done. One told me his father’s message was “absolutely don’t work in the mine.”

To be sure, in the mining museums, one finds statistics on Japan’s national output of coal, and panels noting the contribution of coal to the Japanese economy from Meiji times through the 1960s. And when the issue of wartime labor comes up, the framing is of course one of national or colonial identity, across the spectrum from denial of coercion and discrimination to recognition of it. Although even in such discussions, local identities sneak into the story. In the narrative promoted by the Nagasaki Municipal Tourist Bureau in a manual for guides at Hashima, miners from Korea were indeed brought against their will, but once on site (at Hashima) they were treated as members of the “islander family”. At the Omuta Coal Mining Museum, a prominent panel displays graffiti written on the rice paper sliding doors in the housing for Korean workers. The residents inscribe desperate longing to return not to Korea but to their specific hometowns.

Thus, in the public history of industrial heritage, as in so many other realms, context is all—the context in which identities are presented, or that which is presented to a guide by the visitor. Identities are fluid, multiple, and mutable.

Happy childhood image of 1950s at Gunkanjima Digital Museum

Omuta coal museum wall writing from wartime housing for Korean workers

Detail on monument at site of housing for wartime Korean workers at Miike mine

Kurita Toku Mitsubishi Mine employee