Reflections on the International Day of Persons with Disabilities — What December 3 Means to Me as a Sustainability Researcher

Author:Marcin Pawel Jarzebski

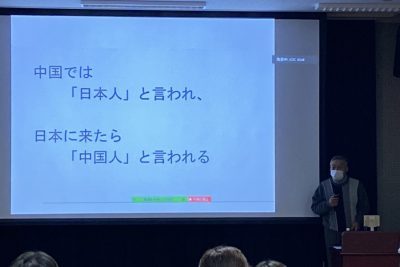

Every year, December 3 marks the International Day of Persons with Disabilities (IDPD), a global initiative established by the United Nations to promote the rights, well-being, and inclusion of persons with disabilities across all spheres of society. The 2025 UN theme have emphasized Fostering disability inclusive societies for advancing social progress — reminding us that inclusion is not symbolic; it is structural, and it requires leadership of change. This year, IDPD held a particularly deep meaning for me. On December 3, 2025, I was in Shanghai, delivering a keynote speech at the Entrepreneurs for Disability Forum, speaking about the role of sustainability and AI in education and research — and how these tools can empower inclusion when designed responsibly. The forum’s theme, “Inclusive Growth, Sustainable Future,” which is aligned with my academic work, but also with my personal journey.

Entrepreneurs for Disability Forum, Shanghai

When Disability Becomes Lived Experience

For many years, my research has explored aging, shrinking societies, and sustainability. I have studied how populations change, how institutions adapt, and how support systems evolve. Together with colleagues at Tokyo College, such as the late Dr. Mark Bookman (whom I will look to as a role model and hero), we often discussed how aging societies naturally move closer to disability, especially how the body weakens, mobility changes, and social support becomes essential. But it was only when I myself began using a wheelchair, experiencing paralysis of my legs and hands, and depending on new social care and assistive devices, that these ideas from theory became my reality.

Suddenly, disability was not a topic of research — it was my daily life. At the same time, I experienced extraordinary support from the University of Tokyo, especially Office for Disability Equity (ODE) , whose assistance allowed me to continue teaching, travelling for research, and carrying out academic duties despite new physical challenges. Their work is quiet but essential, a model of how institutions can empower researchers rather than marginalize them.

Why Disability Matters for Sustainability Science

We cannot talk about sustainability without talking about inclusion.

A sustainable society is one where everyone, regardless of ability, can participate in education, contribute to research, access employment, and move freely. My lived experience made this clearer than ever. In sustainability science, we often emphasize resilience — the capacity of systems to absorb shocks and continue functioning. But isn’t disability the clearest expression of resilience at the individual and societal level? How does a society support people whose abilities change unexpectedly? How do universities enable researchers with disabilities to continue contributing their expertise? How can AI and technological innovation reduce dependency rather than create new barriers? Disability is not an exception but it is a universal human condition, one that almost all of us will experience through illness, accident, or aging.

If sustainability science ignores disability, it ignores the future.

Aging, Disability, and Human–Nature Relationships

As part of my ongoing research funded by JSPS Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (23K11530), I am also examining how older people interact with nature, and how demographic change influences the ways communities engage with forests, satoyama landscapes, and conservation practices. Aging does not only change the body — it changes how we move through natural environments, how we access ecosystem services, and how we participate in stewardship activities. Through this project, I aim to understand how aging and declining population densities reshape human–nature relationships, and what forms of support or innovation are needed so that older and disabled people can continue to benefit from and contribute to nature. This research has become even more meaningful since experiencing disability myself; it helped me see that inclusive design is not only an urban challenge but also a landscape and ecological challenge, especially in societies that are rapidly aging.

Satoyama forest management activities conducted by senior citizens (Kashiwa City, Chiba Satoyama Trust NPO)

Disability as a Shared Future, Not a Minority Issue

One of the biggest misunderstandings about disability is thinking of it as something that happens to “others.” But disability is part of the natural trajectory of human life. Most of us will eventually depend on:

• mobility support,

• assistive technologies,

• accessible infrastructure,

• or social care systems.

This reality connects disability research with aging research, demographic change, and sustainability.

My experiences — moving through airports with a wheelchair, planning research trips with accessibility in mind, depending on other people for support — reshaped how I think about society. They taught me humility, empathy, and the importance of designing systems that allow everyone to thrive.

Becoming an Advocate Through Experience

Before all this, I studied aging, resilience, and adaptive systems.

After experiencing disability firsthand, I found myself speaking not only as a researcher but also as an advocate — for rights, for access to education, for inclusive research environments, and for a future where sustainability and disability inclusion are inseparable.

What December 3 Should Inspire in All of Us

The International Day of Persons with Disabilities is not a celebration of disability itself.

It is a celebration of human dignity, resilience, and the right to participate fully in society.

It reminds us that:

• Inclusion is sustainability.

• Accessibility is innovation.

• Disability is a universal experience.

• And support from institutions — like UTokyo’s Office for Disability Equity (ODE) — can transform lives and careers.

Most importantly, it reminds us that we all have a role to play in shaping societies where every person, at every stage of life, can contribute, grow, and be respected.

This is the future I am committed to — as a researcher, as an educator, and now, as someone who understands disability not only through research, but through lived experience.