Curating Gender and Sexuality: Reflections on the Ōoku Exhibition at Tokyo National Museum

On September 9th, 2025, six members of Tokyo College’s Gender, Sexuality & Identity collaborative research group visited the Ōoku: Women of Power in Edo Castle exhibition at the Tokyo National Museum. The ōoku were living quarters in Edo Castle where the wives and ladies-in-waiting of the shoguns resided during the Edo era (1603-1868). As a hidden and secretive space, the ōoku became a subject of curiosity and speculation, inspiring artists and writers—from the Edo period through the present—to imagine its world in woodblock prints, Kabuki plays, novels, manga, television dramas, and other media. The exhibition’s goal was then to provide a fuller picture of this veiled past through sharing historical records and artifacts such as personal belongings, clothing, and musical instruments.

However, rather than go simply to view the content of the exhibition, our group wanted to analyze the ways that gender and sexuality were being constructed in the space—by the artists, the curators, and the museum visitors. We also hoped to reflect on the politics of memory, considering what the exhibition organizers chose to highlight, downplay, or leave out in the exhibition and its significance to contemporary discussions of gender and sexuality in Japan. The following are some of our observations from the excursion.

Interpreting the Unseen

Hee Eun Kwon, Postdoctoral Fellow, Tokyo College

The Ōoku exhibition, divided into four chapters, opened with an ambitious promise to reveal the inner truth of Edo Castle’s women’s quarters. The first chapter, “The Ōoku in Popular Imagination”, greeted visitors with an artificial bridge leading toward a panoramic screen of the castle’s four seasons. In a later area, a Tokugawa sugoroku board underscored the era’s unironic social ambition: marriage as the ultimate goal.

In “The Founding and Structure of Ōoku,” the historical records were remarkable, though the absence of translations limited accessibility. Much of their richness was lost to non-Japanese visitors, who drifted past with only a vague sense drawn from the brief titles.

The later chapters, which explored personal belongings and daily life, were visually captivating, featuring intimate items such as kakefukusa, seasonal kimonos, miniature dolls from the Doll Festival, and ornate costumes for in-castle Kabuki performances. Albeit their intricacy and beauty, the context was sparse. One label noted that the costumes “hint at the financial power Lady Nori must have held” then ended abruptly – a recurring tendency throughout the explanations.

For an exhibition claiming to offer “academic insight,” it left much to be desired. What did it mean for women in the Ōoku to “use their intelligence to seize power” within such a rigidly male world? Like the opening bridge that barred visitors from crossing to the illusory castle beyond the screen, the Ōoku’s inner “truths” remained largely out of reach, inviting curiosity but offering few revelations.

Perhaps most notable was the quiet reverence of the visitors, many elderly, studying each caption and pattern – some even with binoculars. As I write from Hibiya Midtown, overlooking the Imperial Palace, I suspect that it is precisely this fascination and the enduring yearning to see beyond that keeps the Ōoku alive in Japan’s imagination.

In the Shadow of Shogun

Eri Kitada, Postdoctoral Fellow, Tokyo College

As a big fan of the manga and anime Ōoku (a queered reimagining of the shogunate through gender inversion), I was very excited to see this exhibition. What struck me most was a panel introducing the official wives of successive shoguns. Having grown up in the Japanese public education system, I could recognize many of the shoguns’ names, but I realized that I did not know a single one of their wives. My history textbooks never helped me imagine the life of Tsukiyama-dono, the wife of Tokugawa Ieyasu, founder of the Edo shogunate. According to the panel, she suffered violence at his hands—an account that sharply contrasts with the prevailing image of Ieyasu as a patient and composed figure, especially when compared with his contemporaries, Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Another story that stayed with me was that of Yoshiko, wife of the seventh shogun, Ietsugu. At the age of two, she was betrothed to him, then seven years old. He died soon after, and from the age of two until her death she lived as a widow. Most of the marriages described on the panel seemed unhappy. Without these marriages into the shogunate family, however, we may have few records of these women’s lives.

Such brief fragments made me feel sadness for these women, whose lives were so heavily determined by the lottery of marriage within a “premodern” feudal order before the Meiji Restoration. At the same time, their names and short biographies stood as a powerful testament to their neglected presence. My own lack of education and imagination about even these extremely privileged women made me reflect on how historical narratives are constructed in profoundly gendered ways that prioritize men’s perspectives.

It was a meaningful experience to visit this popular exhibition with my TC colleagues—sharing our thoughts and critiques, fielding their questions, and engaging with it both as a historian and as someone from Japan.

Searching for Women’s Voices in the Ōoku Exhibition

Shannon Welch, Project Researcher, Tokyo College

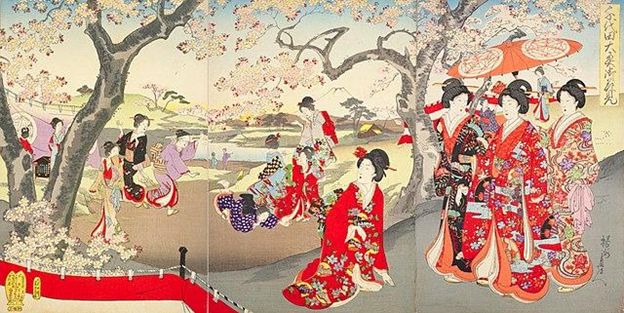

The exhibition described how the ōoku was “a place longed for by the common people, yet it remained a hidden world deep within Edo Castle.” The first room provided such examples of longing, displaying imaginative and idealized representations of the ōoku from the Edo period to the present. Moving through the space, I was particularly intrigued by the ukiyo-e woodblock prints depicting scenes in the Edo-era ōoku, which were created mainly by male artists in the Meiji era like Yōshū Chikanobu. Rather than provide glimpses of what life was really like for women in the ōoku, it became clear to me that these prints reflected the gendered and temporal positionalities of their creators. From a modern male perspective, they depicted images of idealized female beauty, often connecting women to the natural world and its four seasons.

The prints made me long to learn more about the women in the ōoku from the perspectives of these women themselves. While the exhibition aimed to “uncover a more truthful picture of the ōoku” and share the “joy, anger, sorrow, and happiness” of these women’s lives, I found it challenging to hear the women’s voices in the exhibition. The objects on display provided hints about their lives but provided little context around their experiences. The biographies of certain wives and women-in-waiting, juxtaposed with the objects, also tended to define these figures primarily in relation to their husbands, rather than on their own terms. Recovering the voices of women in the ōoku, therefore, seemed like a task that remains for future historians.

Seeing beyond a single story

Balawansuk Lynrah, Postdoctoral Fellow, Tokyo College

The exhibition Ōoku: Women of Power in Edo Castle offered a formal remembrance of women who lived within the social and cultural structures of the Edo period. Among the many stories, Princess Yoshiko engaged/married at the age of 2 to the 7th Shogun ‘causing this princess to spend her entire life alone’ stayed with me. Her story stirred both curiosity and unease. I was curious to what it means for a child to be drawn into such familial arrangements.

Adults, through families and institutions, often shape how children should behave, respond, and conform. This image of Princess Yoshiko also made me think deeply about the institutional practices and the roles children play within families, public life, and private spaces, and broader socio-political contexts. It seems to depict that the lives of children, then and now, are often marginalised and folded into adult expectations and authority. This image allows us to see beyond a single story. It invites reflections and urges us to interrogate how histories of power, gender, age, and generation continue to shape our understanding of children’s agency and rights.

Standing before Princess Yoshiko’s portrait, I was reminded of both the limits and possibilities of museum spaces. Exhibitions can sometimes be representational, but they also open space for curiosity. Much like the story of Princess Yoshiko, explanations within museums are limited and they cannot capture the full complexity of lives and experiences. This is why her story, to me, feels incomplete. However, it is precisely this incompleteness that opens space for curiosity. As a result, museum then becomes more than a display. It becomes a starting point encouraging us to question, to read, and to wonder what lies beyond what is shown and what inquiries are relevant in the contemporary world.

The Game of Life

Machi R. de Oliveira, Doctoral Student, The University of Tokyo - Graduate School of Interdisciplinary Information Studies

As I pass through the multiple historical prints beautifully depicting the lives of women in the Ōoku during the Edo period, I see a repetition of scenes and moments that were performances planned to symbolize aesthetic ideals. The images are encoded to fill the eyes with the style and life of those times. The artworks exhibited at the National Museum in Ueno attracted thousands of people even during the weekdays. The place was so packed that some people tried to enter a nonexistent line to catch a glimpse of the images in open scrolls and individual canvases. The amount of the crowd and the difficulty of seeing the images put me in the mode that Clement Greenberg called ‘Unreflected Enjoyment’. In the first room, I had no time to decode the details in the images, so I failed to grasp the underlying facts they conveyed. Everything became entertainment. But in the end, I found that ok, since it is clear how everything lined up is merely planned historical performance. However, as I progress through the exhibition rooms, I meet a familiar piece, not in its content but in its structure. The room dedicated to ‘Sugoroku’ makes me stop and defy the flow of people to look at it in detail. I first learned about the Sugoroku games while studying the Japanese Imperial colonization of the Pacific Islands, where we analysed how one of those games depicted the native people of the islands in comparison to Japanese soldiers and settlers. Sugoroku is a Chinese game somewhat similar to the Game of Life, in which players advance through stages to win. There are various examples of the game associated with the imperial education of children, both in Japan and the Ryukyus. As a way to normalize militarization, various Suguroko were made with warfare as a background. But what I was looking at in the National Museum was a Suguroko depicting a woman's life, spanning stages of life, including traditional practices and music classes, culminating in marriage as the final victory. Sara Ahmed in ‘Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others’ talks about how institutions reproduce racial and gendered norms not only through policies but through everyday bureaucratic and affective practices too. A simple object, such as a game, connects us to joy and ambition. Still, in the case of Sugoroku, it also linked people from that time to ideologies by embedding them in material practices and rituals that, despite not seeming violent, became a form of subjection. In those Sugoroku in the National Museum, I see the “formation” of an ideal woman towards marriage as a victory, as a well-planned endeavor in line with Confucian ideals. I look to the past of a country that created marriage as a victory for cis gender people, but today still won’t allow partners with the same gender to achieve such a victory. In the end, unexpectedly, I realized that the item which could most represent ‘unreflected enjoyment’ – a game – actually brought me to do the opposite, making me deeply think about the construction of gender roles and norms in Japan.