Should low tax countries learn to love a minimum tax rate?

Shafik Hebous* and Michael Keen**

Securing agreement on the idea of a common minimum effective corporate tax rate was hard; but agreeing on a number for that minimum was excruciatingly difficult. And the choice seems set to remain highly contentious. Many, of course, think the agreed 15% is ludicrously low. The Argentine Finance Minister, for one, advocated a rate “certainly not less than 21%, and 25% would be even better.” Many low tax countries, on the other hand, think 15% painfully high. There seems to be clear conflict of interest at work, between high tax countries set to gain from the minimum and low tax countries sure to lose.

But things are not so simple, and the scope for mutual benefit may be greater than often realized. The reason, as we explain in our recent CBT working paper, is that high tax countries, even if not directly constrained by the minimum, may increase their rates (or not cut them so much) in response to the forced rate increases in low tax countries that are directly affected. This then has ‘spillback’ effects benefiting those low tax countries, with the result that they may end up gaining from being obliged to set their rate higher than they wanted to.

How low tax countries can gain from a minimum rate

How come? Imagine, for instance, you are a low tax country, benefiting from profit shifting in your direction, and have decided that the best rate for you is, to pick a number at random, 12.5%. Now you are obliged to raise your rate by a tiny amount, to 12.6 percent. As a result, you lose out from having less inward profit shifting but you also gain from charging the tax base that remains at a higher rate. But you had already balanced those two effects in deciding that 12.5% was the best choice. So increasing that to 12.6% makes no real difference to you. And that’s not all that happens. The high tax country is likely to raise its rate, since your increased rate means it can do so with less fear that its tax base will leak away in your direction. That higher rate abroad is good for you, because it shifts profits back in your direction. And since you did not initially choose that foreign rate, this spillback impact is not approximately zero: it is positive. So, overall, you, the low tax country, gain.

This is a pretty neat argument. But learning that a low tax country may gain from an infinitesimally small forced increase in its tax rate is not much help when what is in prospect is forced increases that are really material. So what happens to the well-being of the low tax country as we consider increasingly high minimum rates?

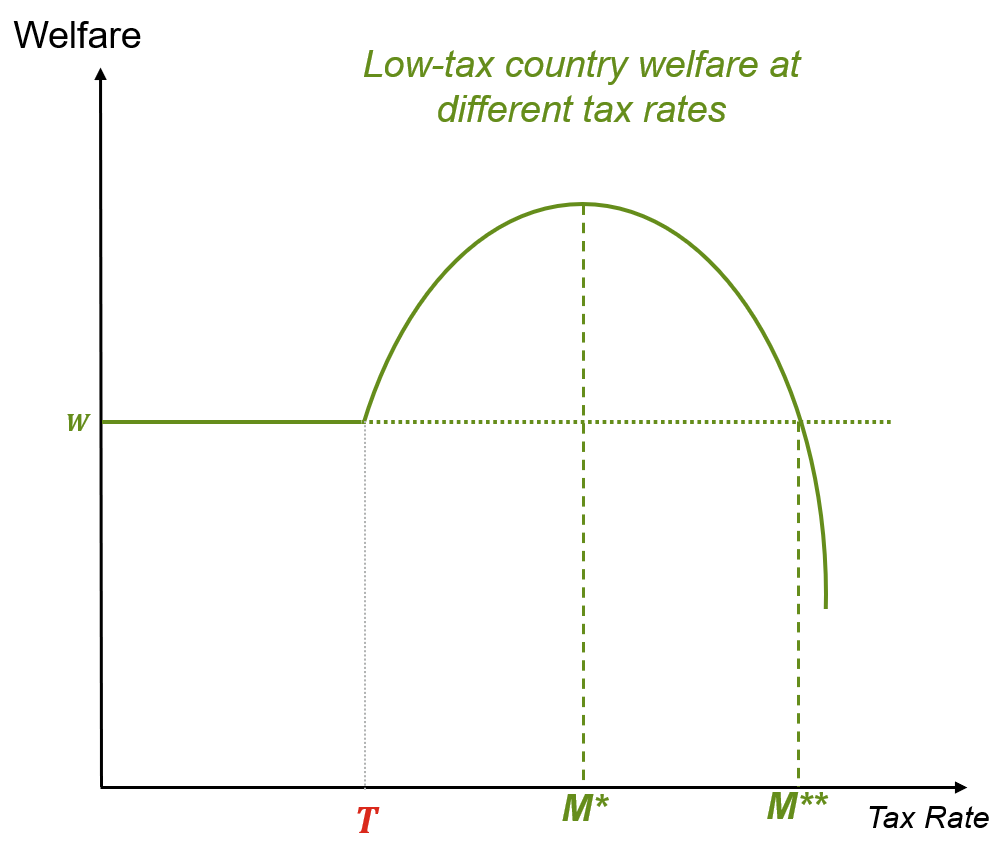

The figure shows a plausible story. Without a minimum, the low tax country sets a tax rate of T and enjoys welfare (meaning the value it attaches to its aggregate tax revenue and private after-tax income) of W. As we just saw, welfare in the low tax country increases as the minimum M rises slightly above T. This welfare increase continues for a while as we imagine increasing the minimum, reflecting the balance between the same two effects as above. The upside of a higher minimum rate is collecting more revenue on whatever tax base is left. (Here we suppose that the low tax country imposes the minimum itself, rather than leaving tax revenue on the table for the other country to pick up by levying a top up tax). The downside, is that this base becomes narrower, as profit shifting into the low tax country falls. At first, the upside dominates. At some level of the minimum rate, however—M* in the figure—these effects just balance out, and welfare in the low tax country reaches a peak: this is the minimum rate that the low tax country should most prefer. With further increases in the minimum, the downside comes to dominate and welfare in the low tax country then starts to fall, until beyond some point M** it is actually lower than it was before the minimum was introduced. Bottom line: the minimum can be set as high as M** and still be better for the low tax country than having no minimum at all.

Note: M* is the minimum rate that leads to the highest possible welfare for the low tax country. Any minimum rate greater than M** leaves the low tax country worse off than it was with no minimum. Source: Hebous and Keen (2021).

How high (and how plausible)?

So, coming back to actual numbers, how high might M* and M** be? Suppose that the low tax rate is initially 12.5% while the rate in the high tax country is in the low 20%s. Then—depending on such things as the social value attached to tax revenue relative to private incomes—rough calculations reported in the paper suggest that the most preferred rate for the low tax country M* might be 15-17%. And a minimum M** as high as even 17-20% might still leave it better off than it was without the minimum. These numbers are far from being engraved in stone, but they do suggest that, within the terms of the recent (and doubtless continuing debate), the scope for a convergence of interests, rather than a conflict, may be greater than commonly realized.

Some worry that high tax countries will respond to tax increases in countries affected by the minimum not by raising their rates, as in the story above, but by cutting them. The minimum becomes not just a floor but also something like a ceiling, and the spillback effect on low tax countries would then be adverse. That is indeed a logical possibility. But past experience (and concurrent discussions in some large countries) suggest otherwise: the process of tax competition has been one in which countries respond to rate cuts elsewhere by cutting their own rates, not by increasing them.

The important point, in any case, is the more general one: among the many consequences of a minimum tax is a change in the underlying strategic structure of the tax competition game between governments. And the reactions of high tax countries, much ignored in the recent debate, are likely to be critical to the impact of this landmark innovation in international tax policies.

* International Monetary Fund, Washington DC.

** Tokyo College, University of Tokyo; Centre for Business Taxation, Oxford: CERDI, Université Clermond Auvergne; Institute for Fiscal Studies, London.