Love, coffee and word associations

When you smell coffee, what picture appears in your mind? What do you feel? What time of the day do you imagine?

Distinctive smells like the smell of coffee tend to trigger strong associations. In the same way as the smell of coffee is associated with the process of waking up in the morning or staying awake during the day, words ‘coffee’ and ‘morning’ or ‘coffee’ and ‘break’ can be associated with each other.

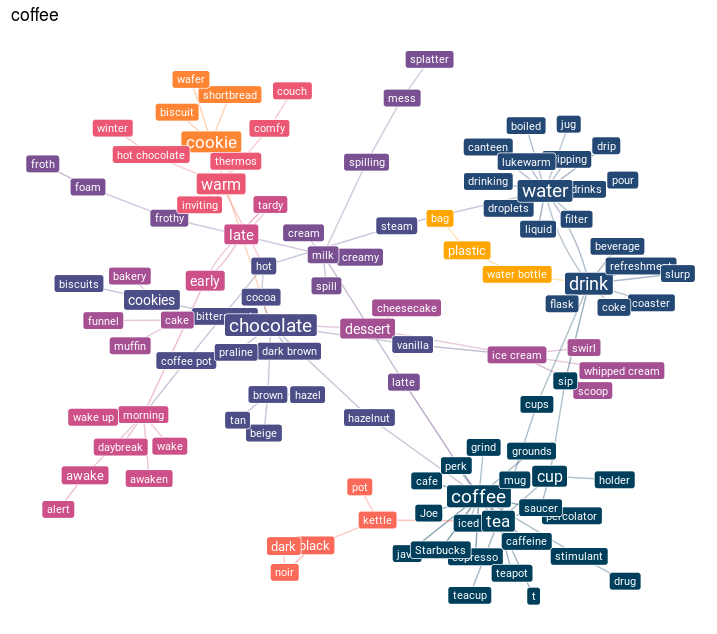

Fig. 1 The English associative neighbourhood of the word ‘coffee’

The character of associative connections between words vary. Some words are strongly linked in our minds because their real-life equivalents are frequently used or mentioned together like ‘salt’ and ‘pepper’. On the other hand, words that we often see as collocations or parts of complex words also tend to be associated with each other like ‘saltwater’ in English or sukima kaze (‘draught’) in Japanese. Associations can also have more complex relationships – relationships of opposition like ‘outside’ and ‘inside’ or subordination like ‘color’ and ‘red’. Another notable type of associative connections are words that come to our minds as typical characteristics of a cue word, e.g. as ‘bitter’ to ‘coffee’.

In some cases, culture, society, or individual life-story might influence the associative connections of words in our minds. For example, sakura (‘cherry blossom’) for a Japanese native speaker can be associated with the whole cluster of words related to spring, new school year, hanami picnics. However, the same set of associations would not appear if they are taken out of the context of Japanese culture and society. Each of us also has individual word associations based on the memories, own linguistic features, or language of the people we know. For example, a frequently used word or a whole manner of speech could be strongly associated with a friend, colleague, or relative.

Understanding of the conceptual structures underlying our thought and speech, detection of the meaning of words, and the way they are categorized in our minds have been one of the central questions for scholars since ancient times. In ‘On Interpretation’ Aristotle expresses the idea that words represent mental conceptual structures: ‘Spoken words are the symbols of mental experience’. This idea inspired a centuries-long scientific search for what and how words mean, where the concepts are stored and how they can be traced.

Access to social, cultural, and semantic knowledge is the reason why word associations have been considered a source to get access to processes of the human mind and to model its conceptual structures for more than hundred years. The first examples of such use of the associations can be found in the works of such psychologists as Carl Jung and Francis Galton. Initially, specific pairs of associations and strength of connections between words were the main object of analysis. For instance, Jung used word associations as a technique to get access to and then analyse the manifestations of subconscious of his patients. Later the interest of researchers shifted towards the conceptual structures represented by all the words connected to the cue word via associations or context. Theory development stimulated the creation of word association datasets or ‘word association norms’, but mainly for English and other European languages. Though these association norms served as extensively and productively used sources for further research, the data collected for the datasets were predominantly obtained through paper or offline computer tasks with university students as participants, making data organization process quite time-consuming and participants’ age and education range relatively limited.

The development of technology in recent decades has played a big role in the ways word association data arecollected, organized, and studied. Today researchers all over the world can collaboratively learn various aspects of the human mind through analysis of word associations in different languages. A complex of these aspects is usually referred to as ‘mental lexicon’. Mental lexicon is also sometimes called one’s ‘mind dictionary’. In psychology and cognitive linguistics ‘mental lexicon’ is a term used to refer to information on the meaning, syntactic features, pronunciation, and sociolinguistic knowledge stored in our minds. With the appearance of accessible software and hardware allowing storage and analysis of large amounts of data, and with the shift towards online word association experiments, the researchers can build large scale models of the mental lexicon and investigate its conceptual structure with datasets counting over 5million responses, e.g. English Small World of Words.

Though the approaches to the analysis of word associations have changed over the century, the typical task of a word association experiment remains the same – participants are asked to write down the first word(s) which come to their mind when they see a cue word. Such a word association experiment is usually called a ‘free word association experiment’, as the participants have the freedom to answer with any association they come up with.

This simple task gives researchers material to investigate a great variety of features of the mental lexicon and make discoveries about memory, language development, creativity, and individual differences.

One such discovery is that the nature of the associations produced by the participants is interconnected with their age. This discovery was confirmed in works on associations in different languages, e.g. Portuguese, Japanese, Spanish. Research demonstrates that through our lifetime from childhood to adulthood, we don’t only grow our lexicon, we enrich our mental lexicon with new connections. In other words, we learn more words and we connect words more and more with each other when we grow up. Further observation of differences in responses of participants of different ages is thought to be a tool to learn about the development of and changes in the ways we understand and conceptualize things through the lifetime.

Associations reveal differences not only between age groups but also highlight gender-based variation in perception of the seemingly universal fundamental concepts, such as ‘love’.

Fig. 2 ‘Love as mutual misunderstanding’

As you can see from the Fig. 2 ‘Love as mutual misunderstanding’, responses of female and male participants of the English version of the Small World of Words word association study demonstrate the scale of difference between male and female participants. Associations of male participants are mostly focused around the physical aspects of love, while associations of female participants are family-focused. The concept of ‘love’ that at the first glance is supposed to be universal, appears to be perceived in absolutely different terms by native speakers of the same language depending on their gender. On the other hand, there are languages like Japanese where the whole cluster of words, e.g., renai, ai, koi, aijoo, suki, covers the range of meanings English ‘love’ has. With such variation of ‘love’ expressions, it would be even more exciting to observe whether the gender difference revealed in English data will appear in Japanese.

These and many more observations and further in-depth studies can only be conducted with sufficient datasets, giving the researchers a big sample from a different age, gender, education level, regional groups of participants. In the international project of Small World of Words, such samples have already been collected for English, Dutch and Spanish. Over 100, 000 volunteers took part in each of the projects. Moreover, the English project received the “Best Paper of the Year” award from the Psychonomic Society in 2019, and its data have already been downloaded by over 2000 researchers.

This fall we are starting a Japanese version of the Small World of Words project. In our project, we will investigate the features of the Japanese mental lexicon at the scale it has not been looked at before. Along with research on gender- age- region- based differences in Japanese native speakers’ word associations, the Japanese Small World of Words will document and investigate such fundamental concepts of the Japanese mental lexicon as time, space, emotions, human relations, and family.

Plans for the future development of the project include cross-cultural and cross-linguistic comparison both in terms of the structure of the mental lexicon and of individual conceptual structures. In the long-term perspective, we are planning to create multilingual tools for science-based language learning support.

You can try the Japanese version of the Small World of Words now. The word associations take only 5 minutes of your time. You might or might not learn something new about yourself, but what we do know is that your contribution to this study will help us to learn the nuances of the Japanese mental lexicon, its culturally specific features, and similarities with other languages. Want to know more about the project?

Find us through the project’s website or Facebook page.